Seligor's Castle, fun for all the children of the world.PRINCESS ON THE GLASS HILL

ONCE on a time there was a man who had a meadow, which lay high up on the hill-side,

and in the meadow was a barn, which he had built to keep his hay in.

Now, I must tell you there hadn't been much in the barn for the last year or two,

for every St. John's night, when the grass stood greenest and deepest,

the meadow was eaten down to the very ground the next morning,

just as if a whole drove of sheep had been there feeding on it over night.

This happened once, and it happened twice; so at last the man grew weary of losing his

crop of hay, and said to his sons—for he had three of them,

and the youngest was nicknamed Boots, of course—that now one of them must

just go and sleep in the barn in the outlying field when St. John's night came,

for it was too good a joke that his grass should be eaten, root and blade,

this year, as it had been the last two years. So whichever of them went must

keep a sharp look-out; that was what their father said.

Well, the eldest son was ready to go and watch the meadow; trust him for looking after the grass! It shouldn't be his fault

if man or beast, or the fiend himself, got a blade of grass. So,

when evening came, he set off to the barn, and lay down to sleep;

but a little on in the night came such a clatter, and such an earthquake,

that walls and roof shook, and groaned, and creaked; then up jumped the lad,

and took to his heels as fast as ever he could; nor dared he once look round

till he reached home; and as for the hay, why it was eaten up this year just

as it had been twice before.

The next St. John's night, the man said again it would never do to lose all

the grass in the outlying field year after year in this way, so one of his

sons must just trudge off to watch it, and watch it well too. Well,

the next oldest son was ready to try his luck, so he set off,

and lay down to sleep in the barn as his brother had done before him;

but as night wore on there came on a rumbling and quaking of the earth,

worse even than on the last St. John's night, and when the lad heard it

he got frightened, and took to his heels as though he were running a race.

Next year the turn came to Boots; but when he made ready to go,

the other two began to laugh, and to make game of him, saying,— Next year the turn came to Boots; but when he made ready to go,

the other two began to laugh, and to make game of him, saying,—

"You're just the man to watch the hay, that you are; you who have done nothing

all your life but sit in the ashes and toast yourself by the fire."

But Boots did not care a pin for their chattering, and stumped away,

as evening drew on, up the hill-side to the outlying field.

There he went inside the barn and lay down; but in about an hour's time the barn

began to groan and creak, so that it was dreadful to hear.

"Well," said Boots to himself, "if it isn't worse than this,

I can stand it well enough."

A little while after came another creak and an earthquake, so that the

litter in the barn flew about the lad's ears.

"Oh!" said Boots to himself, "if it isn't worse than this,

I daresay I can stand it out."

But just then came a third rumbling, and a third earthquake, so

that the lad thought walls and roof were coming down on his head;

but it passed off, and all was still as death about him.

"It'll come again, I'll be bound," thought Boots; but no,

it did not come again; still it was and still it stayed; but

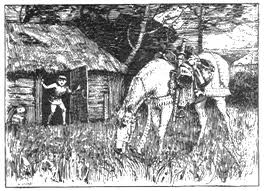

after he had lain a little while he heard a noise as if a horse were

standing just outside the barn-door, and cropping the grass.

He stole to the door, and peeped through a chink, and there,

stood a horse feeding away. So big, and fat, and grand a horse,

Boots had never set eyes on; by his side on the grass lay a saddle and bridle,

and a full set of armour for a knight, all of brass, so bright that

the light gleamed from it.

"Ho, ho!" thought the lad it's you, is it, that eats up our hay?

I'll soon put a spoke in your wheel; just see if I don't."

So he lost no time, but took the steel out of his tinder-box,

and threw it over the horse; then it had no power to stir from the spot,

and became so tame that the lad could do what he liked with it.

So he got on its back, and rode off with it to a place which no one knew of,

and there he put up the horse. When he got home his brothers laughed,

and asked how he had fared?

"You didn't lie long in the barn, even if you had the heart to go so far as the field."

"Well," said Boots, "all I can say is, I lay in the barn till the sun rose,

and neither saw nor heard anything; I can't think what there was in the

barn to make you both so afraid."

"A pretty story!" said his brothers; "but we'll soon see how you have watched

the meadow;" so they set off; but when they reached it,

there stood the grass as deep and thick as it had been over night.

Well, the next St. John's eve it was the same story over again;

neither of the elder brothers dared to go out to the outlying field to watch the crop;

but Boots, he had the heart to go, and everything happened just as

it had happened the year before. First a clatter and an earthquake,

then a greater clatter and another earthquake, and so on a third time;

only this year the earthquakes were far worse than the year before.

Then all at once everything was as still as death, and the lad heard how something

was cropping the grass outside the barn-door, so he stole to the door,

and peeped through a chink; and what do you think he saw?

why, another horse standing right up against the wall, and

chewing and champing with might and main. It was far finer and fatter than

that which came the year before, and it had a saddle on its back,

and a bridle on its neck, and a full suit of mail for a knight lay by its side,

all of silver, and as grand and you would wish to see.

"Ho, ho!" said Boots to himself; "it's you that gobbles up our hay, is it?

I'll soon put a spok e in your wheel;" and with that he took the steel out

of his tinder-box, and threw it over the horse's crest, which stood as still

[96] as a lamb. Well, the lad rode this horse, too, to the hiding-place where

he kept the other one, and after that he went home. e in your wheel;" and with that he took the steel out

of his tinder-box, and threw it over the horse's crest, which stood as still

[96] as a lamb. Well, the lad rode this horse, too, to the hiding-place where

he kept the other one, and after that he went home.

"I suppose you'll tell us," said one of his brothers, "there's a fine crop

this year too, up in the hayfield."

"Well, so there is," said Boots; and off ran the others to see, and

there stood the grass thick and deep, as it was the year before;

but they didn't give Boots softer words for all that.

Now, when the third St. John's eve came, the two elder still hadn't the heart to

lie out in the barn and watch the grass, for they had got so scared at heart

the night they lay there before, that they couldn't get over the fright;

but Boots, he dared to go; and, to make a long story short, the very same thing

happened this time as had happened twice before. Three earthquakes came, one

after the other, each worse than the one which went before, and when the last came,

the lad danced about with the shock from one barn wall to the other;

and after that, all at once, it was still as death. Now when he had lain a

little while he heard something tugging away at the grass outside the barn,

so he stole again to the door-chink, and peeped out, and there stood a horse close

outside—far, far bigger and fatter than the two he had taken before.

"Ho, ho!" said the lad to himself, "it's you, is it, that comes here eating

up our hay? I'll soon stop that—I'll soon put a spoke in your wheel."

So he caught up his steel and threw it over the horse's neck, and

in a trice it stood as if it were nailed to the ground, and Boots could

do as he pleased with it. Then he rode off with it to the hiding-place where

he kept the other two, and then went home. When he got home his two brothers made game of him as they had

done before, saying they could see, he had watched the grass well,

for he looked for all the world as if he were walking in his sleep,

and many other spiteful things they said, but Boots gave no heed to them,

only asking them to go and see for themselves; and when they went,

there stood the grass as fine and deep this time as it had been twice before.

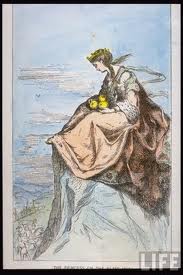

Now, you must know that the king of the country where Boots lived had a daughter,

whom he would only give to the man who could ride up over the hill of glass,

for there was a high, high hill all of glass, as smooth and slippery as ice,

close by the king's palace. Upon the tip-top of the hill the king's daughter was to sit,

with three golden apples in her lap, and the man who could ride up and

carry off the three golden apples was to have half the kingdom,

and the Princess to wife. This the king had stuck up on all the church-doors

in his realm, and had given it out in many other kingdoms besides. Now,

this Princess was so lovely that all who set eyes on her fell over head

and ears in love with her whether they would or no. So I needn't tell you how all

the princes and knights who heard of her were eager to win her to wife,

and half the kingdom beside; and how they came riding from all parts of

the world on high prancing horses, and clad in the grandest clothes, for

there wasn't one of them who hadn't made up his mind that he, and he alone,

was to win the Princess.

So when the day of tri al came, which the king had fixed, there was such

a crowd of princes and knights under the glass hill, that it made one's

head whirl to look at them; and every one in the country who could even crawl

along was off to the hill, for they all were eager to see the man who was

to win the Princess. So the two elder brothers set off with the rest;

but as for Boots, they said outright he shouldn't go with them,

for if they were seen with such a dirty changeling, all begrimed

with smut from cleaning their shoes and sifting cinders in the dusthole,

they said folk would make game of them. al came, which the king had fixed, there was such

a crowd of princes and knights under the glass hill, that it made one's

head whirl to look at them; and every one in the country who could even crawl

along was off to the hill, for they all were eager to see the man who was

to win the Princess. So the two elder brothers set off with the rest;

but as for Boots, they said outright he shouldn't go with them,

for if they were seen with such a dirty changeling, all begrimed

with smut from cleaning their shoes and sifting cinders in the dusthole,

they said folk would make game of them.

"Very well," said Boots, "it's all one to me. I can go alone, and stand

or fall by myself."

Now when the two brothers came to the hill of glass the knights and

princes were all hard at it, riding their horses till they were all in a foam;

but it was no good, by my troth; for as soon as ever the horses set foot

on the hill, down they slipped, and there wasn't one who could get a yard

or two up; and no wonder, for the hill was as smooth as a sheet of glass,

and as steep as a house-wall. But all were eager to have the Princess and half the

kingdom. So they rode and slipped, and slipped and rode, and still it

was the same story over again. At last all their horses were so weary that

they could scarce lift a leg, and in such a sweat that the lather dripped from them,

and so the knights had to give up trying any more. So the king was just thinking that

he would proclaim a new trial for the next day, to see if they would

have better luck, when all at once a knight came riding up on so brave a steed

that no one had ever seen the like of it in his born days, and the knight had mail

of brass, and the horse a brass bit in his mouth, so bright that the sunbeams shone

from it. Then all the others called out to him he might just as well

spare himself the trouble of riding at the hill, for it would lead to no good;

but he gave no heed to them, and

[99] put his horse at the hill, and went up it like nothing for a good way,

about a third of the height; and when he had got so far, he turned his horse round and

rode down again. So lovely a knight the Princess thought she had never yet seen;

and while he was riding, she sat and thought to herself—

"Would to heaven he might only come up, and down the other side."

And when she saw him turning back, she threw down one of the golden apples

after him, and it rolled down into his shoe. But when he got to the bottom of the

hill he rode off so fast that no one could tell what had become of him.

That evening all the knights and princes were to go before the king,

that he who had ridden so far up the hill might show the apple which the

princess had thrown, but there was no one who had anything to show.

One after the other they all came, but not a man of them could show the apple.

At even the brothers of Boots came home too, and had such a long story to tell

about the riding up the hill.

"First of all," they said, "there was not one of the whole lot who could get so

much as a stride up; but at last came one who had a suit of brass mail, and

a brass bridle and saddle, all so bright that the sun shone from them a mile off.

He was a chap to ride, just! He rode a third of the way up the hill of glass, and

he could easily have ridden the whole way up, if he chose; but

he turned round and rode down, thinking, maybe, that was enough for once."

"Oh! I should so like to have seen him, that I should," said Boots, who

sat by the fireside, and stuck his feet into the cinders as was his wont.

"Oh!" said his brothers, "you would, would you? You look fit to keep company with s uch

high lords, nasty beast that you are, sitting there amongst the ashes." uch

high lords, nasty beast that you are, sitting there amongst the ashes."

Next day the brothers were all for setting off again, and Boots begged them this time,

too, to let him go with them and see the riding; but no,

they wouldn't have him at any price, he was too ugly and nasty, they said.

"Well, well!" said Boots; "if I go at all, I must go by myself. I'm not afraid."

So when the brothers got to the hill of glass, all the princes and knights

began to ride again, and you may fancy they had taken care to shoe their

horses sharp; but it was no good,—they rode and slipped, and slipped

and rode, just as they had done the day before, and there was not one who

could get so far as a yard up the hill. And when they had worn out their horses,

so that they could not stir a leg, they were all forced to give it up

as a bad job. So the king thought he might as well proclaim that the riding

should take place the day after for the last time, just to give them one chance more;

but all at once it came across his mind that he might as well wait a little longer,

to see if the knight in brass mail would come this day too. Well, they saw nothing

of him; but all at once came one riding on a steed, far, far, braver and finer than that

on which the knight in brass had ridden, and he had silver mail, and a silver

saddle and bridle, all so bright that the sunbeams gleamed and glanced from them far

away. Then the others shouted out to him again, saying he might as well

hold hard, and not try to ride up the hill, for all his trouble would be thrown away;

but the knight paid no heed to them, and rode straight at the hill,

and right up it, till he had gone two-thirds of the way, and then he wheeled his horse

round and rode down again. To tell the truth, the Princess liked him still better

than the knight in brass, and she sat and wished he might only be able to come right

up to the top, and down the other side; but when she saw him turning back,

she threw the second apple after him, and it rolled down and fell into his shoe.

But as soon as ever he had come down from the hill of glass,

he rode off so fast that no one could see what became of him.

At even, when all were to go in before the king and the Princess,

that he who had the golden apple might show it; in they went, one after the other,

but there was no one who had any apple to show, and the two brothers,

as they had done on the former day, went home and told how things had gone,

and how all had ridden at the hill and none got up.

"But, last of all," they said, "came one in a silver suit,

and his horse had a silver saddle and a silver bridle. He

was just a chap to ride; and he got two-thirds up the hill,

and then turned back. He was a fine fellow and no mistake;

and the Princess threw the second gold apple to him."

"Oh!" said Boots, "I should so like to have seen him too, that I should."

"A pretty story!" they said. "Perhaps you think his coat of mail was as bright

as the ashes you are always poking about, and sifting, you nasty dirty beast."

The third day everything happ ened as it had happened the two days before.

Boots begged to go and see the sight, but the two wouldn't hear of

his going with them. When they got to the hill there was no one who could

get so much as a yard up it; and now all waited for the knight in silver mail,

but they neither saw nor heard of him. At last came one riding on a steed,

so brave that no one had ever seen his match; and the knight had a suit of golden mail,

and a golden saddle and bridle, so wondrous bright that the sunbeams gleamed from

them a mile off. The other knights and princes could not find time to call

out to him not to try his luck, for they were amazed to see how grand he was.

So he rode right at the hill, and tore up it like nothing, so that the Princess

hadn't even time to wish that he might get up the whole way. As soon as

ever he reached the top, he took the third golden apple from the Princess' lap,

and then turned his horse and rode down again. As soon as he got down,

he rode off at full speed, and was out of sight in no time. ened as it had happened the two days before.

Boots begged to go and see the sight, but the two wouldn't hear of

his going with them. When they got to the hill there was no one who could

get so much as a yard up it; and now all waited for the knight in silver mail,

but they neither saw nor heard of him. At last came one riding on a steed,

so brave that no one had ever seen his match; and the knight had a suit of golden mail,

and a golden saddle and bridle, so wondrous bright that the sunbeams gleamed from

them a mile off. The other knights and princes could not find time to call

out to him not to try his luck, for they were amazed to see how grand he was.

So he rode right at the hill, and tore up it like nothing, so that the Princess

hadn't even time to wish that he might get up the whole way. As soon as

ever he reached the top, he took the third golden apple from the Princess' lap,

and then turned his horse and rode down again. As soon as he got down,

he rode off at full speed, and was out of sight in no time.

Now, when the brothers got home at even, you may fancy what long stories they told,

how the riding had gone off that day; and amongst other things, they had a deal

to say about the knight in golden mail.

"He just was a chap to ride!" they said; "so grand a knight isn't to be found

in the wide world."

"Oh!" said Boots, "I should so like to have seen him; that I should."

"Ah!" said his brothers, "his mail shone a deal brighter than the glowing

coals which you are always poking and digging at; nasty dirty beast that you are."

Next day all the knights and princes were to pass before the king and the

Princess—it was too late to do so the night before, I suppose—that he who

had the gold apple might bring it forth; but one came after another,

first the princes, and then the knights, and still no one could show the gold apple.

"Well," said the king, "some one must have it, for it was something that we all

saw with our own eyes, how a man came and rode up and bore it off."

So he commanded that every one who was in the kingdom should come up to the palace

and see if they could show the apple. Well, they all came, one after another, but

no one had the golden apple, and after a long time the two brothers of Boots came.

They were the last of all, so the king asked them if there was no one

else in the kingdom who hadn't come.

"Oh, yes," said they; "we have a brother, but he never carried off the golden

apple. He hasn't stirred out of the dust-hole on any of the three days."

"Never mind that," said the king; "he may as well come up to the palace like the rest."

So Boots had to go up to the palace.

"How, now," said the king; "have you got the golden apple? Speak out!"

"Yes, I have," said Boots; "here is the first, and here is the second,

and here is the third too;" and w ith that he pulled all three golden apples out

of his pocket, and at the same time threw off his sooty rags,

and stood before them in his gleaming golden mail. ith that he pulled all three golden apples out

of his pocket, and at the same time threw off his sooty rags,

and stood before them in his gleaming golden mail.

"Yes!" said the king; "you shall have my daughter, and half my kingdom,

for you well deserve both her and it."

So they got ready for the wedding, and Boots got the Princess to wife,

and there was great merry-making at the bridal-feast, you may fancy,

for they could all be merry though they couldn't ride up the hill of glass;

and all I can say is, if they haven't left off their merry-making yet,

why they're still at it.

(Asbjornsen and Moe.)

(from The Blue Fairy Book, edited by Andrew Lang)

|

Of course the little girl in the story isn't Mary Elizabeth, but she dressed up for Seligor so as to make the story brighter. xx Thankyou Molly Jae. (Who just happens to be one of Seligors grand children.)

Mary Elizabeth

Mary Elizabeth Jamison was a little

girl with a long name. She was also very poor. Not only that she was sick she

also wore ragged clothes and was forever cold. This one day she was so she hadn’t

had any supper or dinner, and what’s more she hadn’t had any breakfast. She had

no place to go and nobody to care whether she went there or not. In fact, Mary

Elizabeth had not much of anything but a short peach calico dress, a little red

cotton and wool shawl, and her long name. Oh yes she also possessed a pair of

old red wellies, they were too large for her and they flopped on the pavement

as she walked.

On the night of which I speak she

begged very hard. It is very wrong to beg, we all know that. It is very wrong

to give to beggars, we all know this too: we have been told so many times.

Still, if I had been as hungry as Mary Elizabeth, I presume I would have begged

too.

So here she was peeping into people's

faces, timidly looking away from them; holding out her hand some people pushed

her away, others spoke saying “how ill she looked and she would be better off

dead, poor little thing” Mary Elizabeth Jamison, was sick, but it was only in

her heart - for a very little girl can be heart-sick, especially when she was

getting hungrier each hour than she was the hour before.

The child turned into a short, bright,

showy street, where stood a great hotel. Precisely how she got in nobody knows.

Over the smooth, slippery marble floor, the child crept on. She came to the

office door, and stood still. She looked around her

with wide eyes. She had never seen a place like that. Lights flashed over it,

many and bright. Gentlemen sat in it smoking and reading. They were all warm.

Not one of them looked as if they had, had no dinner no breakfast, or even

supper.

There

was a little noise, a very little one, strange to the warm, bright,

well-ordered room. It was the sound of old wellie-boots, much too large,

flopping on the marble floor. Several gentlemen glanced at their own well shod

and brushed feet.

Mary

Elizabeth stood in the middle of the room in her pink calico dress and red

plaid-shawl. The shawl was tied over her head and about her neck with a ragged

tippet. She looked very funny and round from the back, like the old wooden

women in the Noah's ark. Her bare feet showed in the old toeless wellies. She

began to shuffle about the room, holding out one purple little hand.

One

or two of the gentlemen laughed; some frowned; more did nothing at all; most

did not notice, or did not seem to notice the child. One said, "What's the

matter here?"

Mary

Elizabeth flopped on. She went from one to another, less timidly; a kind of

desperation had taken possession of her. The odours from the dining room came

in of strong hot coffee and strange roast meats. It seemed to her she was so

hungry that if she could not get any supper she should jump up and run into the

kitchen and eat the scraps on the floor..

She

held out her hand, but only said, "I'm hungry!"

A

gentleman called her. He was the gentleman who had asked, "What's the

matter here?" He called her in behind his newspaper, which was big enough

to hide three of Mary Elizabeth, and when he saw that nobody was looking , he

gave her a three-penny piece in a hurry, as if he had done a sin, and quickly

said, "There, there child! Go, go on now!"

Then

he vanished behind his paper again and began to read quite hard and fast, and

to look severe, as one does who never gives anything to beggars.

But

nobody else gave anything to Mary Elizabeth. She shuffled from one to another,

hopelessly. Every gentleman shook his head. One called for a waiter to put her

out. This frightened her, and she stood still.

Over

by the window, in a lonely corner of the great room, a young man was sitting apart

fro the others. Mary Elizabeth had seen the young man when she first came in,

but he had not seen her. He had not seen anything or anybody. He sat with his

elbows on the table, and his face buried in his arms. He was a well dressed

young man, with brown, curling hair. Mary Elizabeth wondered why he looked so

miserable, and why he sat alone. She thought, perhaps, if he were not as happy

as the other gentlemen, maybe he would feel, more, sorry for this cold, hungry

girl. She hesitated for a second then flopped along walking directly up to him. Over

by the window, in a lonely corner of the great room, a young man was sitting apart

fro the others. Mary Elizabeth had seen the young man when she first came in,

but he had not seen her. He had not seen anything or anybody. He sat with his

elbows on the table, and his face buried in his arms. He was a well dressed

young man, with brown, curling hair. Mary Elizabeth wondered why he looked so

miserable, and why he sat alone. She thought, perhaps, if he were not as happy

as the other gentlemen, maybe he would feel, more, sorry for this cold, hungry

girl. She hesitated for a second then flopped along walking directly up to him.

One

or two gentlemen laid down their papers, and watched; they smiled and nodded to

each other. The child did not see them, to wonder why. She went up, and put her

hand upon the young man's arm.

He

started. The brown, curly head lifted itself from the shelter of his arms; a

young face looked sharply at the beggar girl - a beautiful young face it might

have been. It was haggard now, and looked dreadful to look at. He roughly

said,-

"What

do you want?"

"I'm

hungry," said Mary Elizabeth.

"I

can't help that. Go away."

"I

haven't had anything to eat for a whole day - a whole day!" she repeated.

Her

lip quivered, but she spoke distinctly - her voice sounded through the room.

One gentleman after another laid down his paper or his pipe. Several were

watching this little scene.

"Go

away!" repeated the young man irritably. "Don't bother me I haven't

had anything to eat for three days!"

His

face went down in his arms again. Mary Elizabeth stood staring at the brown,

curling hair. She stood perfectly still for some moments. She evidently was

greatly puzzled. She walked away a little distance, then stopped, and thought

it over.

And

now paper after paper and pipe after cigar went down. Every gentleman in the

room began to look on. The young man was not stiller than the rest. The little

figure in pink calico, and the red shawl, and big wellies stood for a moment

silent among them all. The waiter came to take her out, but the gentlemen

motioned him away.

Mary

Elizabeth turned her money over and over slowly in her purple hand. Her hand

shook. The tears came. The smell of the dinner from the dining room grew

savoury and strong. The child put the piece of money to her lips, as if she

could have eaten it; then turned, and, without further hesitation, went back.

She touched the young man - on the bright hair this time - with her trembling

little hand.

The

room was so still now that when she spoke you could hear what she said out in

the corridor, where the waiters stood, and the clerk behind the desk looking to

see who came in and out.

"I'm

sorry you are so hungry. If you haven't had anything for three days you must be

hungrier than me. I've got a silver piece. A gentleman gave it to me. I wish

you would take it. I've only gone one day. You can get some supper with

it, and maybe I can get some, some where else. I wish you'd please to take

it."

Mary Elizabeth stood quite still,

holding out her silver piece. She did not understand the sound and stir that

went all over the bright room. She did not see that some of the gentlemen

coughed, and wiped their spectacles. She did not know why the brown curls

before her came up with such a start nor why the young man's wasted face

flushed red and hot with noble shame.

She did not in the least understand

why he flung the money upon the table, and snatching her in his arms holding

her fast, his face on her plaid shawl sobbing. Nor did she know what could be

the reason that nobody seemed amused to see this gentleman cry; but that the

gentleman who had given her the m oney came up, and some more came up, and they

gathered round, and she in the midst of them; and they spoke kindly, and the

young man stood up, still clinging to her, and said aloud,- oney came up, and some more came up, and they

gathered round, and she in the midst of them; and they spoke kindly, and the

young man stood up, still clinging to her, and said aloud,-

"She's shamed me before you all,

and she's shamed me to myself! I'll learn a lesson from this beggar, so help

me, God!" So then he took the child

upon his knee, and the gentlemen came up to listen, and the young man asked her

what was her name.

"Mary Elizabeth, sir"

"And where do you live, Mary

Elizabeth?"

"Nowhere Sir” she replied

“Then where do you sleep?"

"In Mrs Flynn’s shed, sir. It's

too cold for the cows, so she kindly lets me stay."

"Then who stays with you child?"

"Why nobody sir, I live on my own."

"Where is your mother?"

Mary Elizabeth looked at the floor. “I’m

afraid she died, sir."

"Well what about your father?"

"He is dead also sir. He died in

prison."

"So there is no one at all to

look after you.?"

"Not now sir, I had a brother once,

but he died also." Mary Elizabeth continued -

"I do want my supper," she

added after a pause, speaking in a whisper, as if to herself.

"Wait, then." said the young

man; "I'll see if I can't beg enough to get you your supper."

And truly the young man put the three penny

bit into his hat, then he took out his purse, and put in something that made

less noise than the silver, and something more, and more and more. Then he

passed the hat round the great room, walking still unsteadily, and all the

gentlemen put something into the young man's hat. And truly the young man put the three penny

bit into his hat, then he took out his purse, and put in something that made

less noise than the silver, and something more, and more and more. Then he

passed the hat round the great room, walking still unsteadily, and all the

gentlemen put something into the young man's hat.

When he arrived back to the table he

emptied the hat and counted the money. “Right Mary Elizabeth, there is eight

pounds here, and it is all yours.

"Eight whole pounds” Mary

Elizabeth spluttered, never in her life had she seen eight shillings let alone

eight pounds before.

"Yes, and it is all yours,"

said the young man. "And now I hope you will come and have supper with me.

He sat Mary at the table. “But see this money.” He pointed to the gentleman who

gave her the silver piece. I am sure that if you ask him he will take care of the

money for you. You can trust him. But come now let us eat our supper now"

"The old gentleman came over to

the table. “Mary Elizabeth, it will be my pleasure to help you with this rich

amount and I am sure my wife will know what ought to be done with you, and till

we get it sorted I am sure she will take care of you."

"Thankyou very much,” Said Mary

smiling, but I must first go and thank Mrs Flynn for the shed."

"Oh yes, yes; we'll fix all

that." said the gentleman. "A little girl with eight pounds needn't

sleep in a cow shed anymore. Now do you want that supper?"

"Why, yes, yes I do please." said

Mary Elizabeth.

So the young man took her by the hand,

and the gentleman took her by the other hand and one or two more gentlemen

followed, and they all went out into the dining room, and put Mary Elizabeth in

a chair at a clean white table and asked her what she wanted for her supper.

Mary Elizabeth said that a little dry

toast and a cup of milk would do nicely. Poor Mary Elizabeth, she couldn’t

understand why all the gentlemen laughed. The young man with the brown curls

laughed too, and began to look quite happy. But he ordered chicken, and sauce,

and mashed potatoes, and rolls, and butter, and an ice cream and a cup of tea,

and nuts and raisins, a cake with cream, and an apple and some grapes. all the gentlemen laughed. The young man with the brown curls

laughed too, and began to look quite happy. But he ordered chicken, and sauce,

and mashed potatoes, and rolls, and butter, and an ice cream and a cup of tea,

and nuts and raisins, a cake with cream, and an apple and some grapes.

And would you believe it, Mary

Elizabeth sat in her peach dress and red shawl and ate the whole lot; and why it

didn't kill her nobody knows, but it didn't.

Mary

Elizabeth is a young lady now. She went to work for a lovely lady and gentleman

who treated her like their own daughter, whom they never had. It wasn’t long

until she was fully adopted into the family and now she is engaged to be

married to the son of… well you never will guess… Yes the son of the young gentleman with the curly brown hair. And do you know what I do believe that

they will live happily ever after

|